Singapore’s National Registration Identity Card (NRIC) number (https://www.ica.gov.sg/about-us/our-heritage/Room/national-registration-identification) comprises 7 digits bounded by two letters – S for numbers issued in the 20th century and T for those in this century before the digits followed by a check letter (based on modulo 11 mathematics). It is a happy coincidence that “S” is the 19th letter of the alphabet so fits those born in the 1900s aka 20th century.

When it was first issued in 1966, it was a straight forward running sequence of numbers.

President Yusof Ishak was given S0000001I (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Registration_Identity_Card) following Singapore independence in 1965. See https://www.ica.gov.sg/about-us/our-heritage/Room/national-registration-identification – click on the “Evolution of Identity Cards for details.

These NRIC numbers just proceeded in sequence for a while until I believe 1980 (more on that later).

Officials from the National Registration Office would visit schools and have students 12 years and older to get their NRIC registration done. I know this happened when I was in Primary 6, in 1971, and as a result of this exercise in school, the NRIC numbers of my classmates were in direct running sequence (and it seems to be based on the class roster or where we were seated in class).

My guess as to why the numbers issued then was in sequence was probably because there wasn’t much thinking that went into it. I suppose the birth certificate number could have been used as NRIC number, but that system was messy and inconsistent.

Then from 1968, birth certificates issued started to be in the format: SYYNNNNNC. S for 20th century, YY (two digits of the year) plus 5 digits and C the check letter.

So, S6801234A would mean that the birth was in 1968 and it is the 1,234th birth registered. Generally births are registered within 30 days. And when those individuals reach 12 years of age, which would be 1980, the NRICs issued would just take their birth certificate numbers. Problem solved. May be, may be not.

Now, if you go to data.gov.sg: https://data.gov.sg/datasets/d_6150f21b0892b3fdde546d2a1af2af82/view and look at the births from 1967. The largest recorded births was in 1988 (I am sure it is the Dragon year effect) at 52,957. So, NRICs of that year would be something like S8852957Z (check letter left as exercise – see https://nric.biz/).

Let’s revisit S6801234A. From that, we know the birth year, and from the data set above, there were 47,241 births in 1968. If we divide 47,241 by 12 months, that gives 3936.75, rounding it to 3937. So, chances are that “01234” belongs to someone born in January 1968.

How would that be useful? Let’s consider a bank statement that is sent out to banking customers and “locked” via a combo of NRIC+DOB. These documents don’t have any attempt timeouts and you can iterate until you are successful. Once you have the bank statement “unlocked”, the rest of the data is all for your analysis and (ab)use.

Here’s a presentation given by Shih-Tung Ngiam, 21 years ago (https://www.ngiam.net/NRIC/ppframe.htm) on breaking the NRIC check digit algorithm.

Consider S0000001I, which, when masked is S****001I. Doing it the hard way, one can use a reverse algorithm of the modulo 11 checksum, to give plausible values of the 4 asterisks. There could be a few hits because it would pivot on the “I” and the 001 – i.e., not all numbers that end with 001 would have a check letter “I”.

Or, the smarter way is to build a table that contains ALL of the possible NRIC numbers complete with check letter and use that as a lookup to unmask the NRIC. Or to ride on today’s AI hype, use foundational models to find the values that could fit the 4 asterisks.

This then brings us to what is the value of masking parts of the NRIC as recommended by the Personal Data Protection Commission advisory guidelines (https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/guidelines-and-consultation/2020/02/advisory-guidelines-on-the-personal-data-protection-act-for-nric-and-other-national-identification-numbers) of 2018: https://www.pdpc.gov.sg/-/media/files/pdpc/pdf-files/advisory-guidelines/advisory-guidelines-for-nric-numbers—310818.pdf section 1.3 says:

“1.3 As the NRIC number is a permanent and irreplaceable identifier which can potentially be used to unlock large amounts of information relating to the individual, the collection, use and disclosure of an individual’s NRIC number is of special concern. Indiscriminate or negligent handling of NRIC numbers increases the risk of unintended disclosure with the result that NRIC numbers may be obtained and used for illegal activities such as identity theft and fraud. The retention of an individual’s physical NRIC is also of concern. The physical NRIC not only contains the individual’s NRIC number, but also other personal data, such as the individual’s full name, photograph, thumbprint and residential address.”

And earlier this month, on 14 December 2024, the PDPC says the following:

“Updated as of 14 Dec 2024: In light of the MDDI statement on 13 Dec 2024 outlining the appropriate use and mis-use of NRIC numbers, these Advisory Guidelines will be updated. In the meantime, these guidelines remain valid. The PDPC advises against the use of NRIC numbers by individuals as passwords and the use of NRIC numbers by organisations to authenticate an individual’s identity or set default passwords. For more information, please refer to PDPC’s statement of 14 Dec 2024.”

That last link is replicated here in full:

“PDPC’s reply to media queries on the use of NRIC numbers

14 Dec 2024

We refer to the statement issued by MDDI yesterday outlining the appropriate use and mis-use of NRIC numbers. This statement specifically advises against (a) the use of NRIC numbers by individuals as passwords and (b) the use of NRIC numbers by organisations to authenticate an individual’s identity or set default passwords.

PDPC has previously taken action against organisations which have used NRIC numbers for authentication and breached their data protection obligations. With the public attention drawn to the mis-use of NRIC numbers, we are emphasising these recommendations with added urgency.

Use of NRIC numbers by individuals as passwords

The NRIC number should not be used as a password, just as our names are not used as passwords. Anyone who has done so should immediately change their password.

Most services that require password access will also allow for the password to be changed. This is usually available on the service portal itself. If the change function cannot be found on the service portal, it is best to contact the service provider immediately for advice to change the password.

In deciding on the new password, there are well established good practices to observe. For example, passwords should be set with a minimum level of complexity (e.g. minimum 12 alphanumeric characters with a mix of uppercase, lowercase, numeric, and commonly used phrases or paraphrases.) For more details, please refer to guidelines issued by CSA [https://www.csa.gov.sg/alerts-advisories/Advisories/2022/ad-2022-008].

Use of NRIC numbers by organisations to authenticate an individual’s identity or set default passwords

A person’s name and NRIC number identifies who the person is. Authentication is about proving you are who you claim to be. This requires proof of identity, for example, through a password, a security token or biometric data. As the NRIC number is not a secret, it should not be used by an organisation for authentication purposes. PDPC has consistently taken organisations to task for using NRIC numbers for authentication.

The NRIC number should also not be used as the default password for services provided to an individual. Organisations that have such practices should phase them out as soon as possible.

In designing its authentication practices, organisations should refer to pages 15-16 of the guidelines issued by PDPC on the Guide to Data Protection Practices for ICT Systems. For example, there should be strong requirements for administrative accounts, such as complex passwords or 2-Factor Authentication (“2FA”)/Multi-Factor Authentication (“MFA”), as unauthorised access is one of the most common types of data breaches.

Like any personal identifier, the NRIC number is still subject to the data protection obligations in the PDPA. Therefore, organisations collecting NRIC data must still obtain valid consent and comply with reasonable use and ensure protection.

PDPC’s advisory guidelines for NRIC and National Identification Numbers

We have received questions and feedback from the public following yesterday’s statements by MDDI on the appropriate use and mis-use of NRIC numbers. We are sorry for the confusion caused to the public and will fully address the public’s concerns and questions as soon as possible.

We recognise that the PDPC advisory guidelines for NRIC and National Identification Numbers needs to be updated to be aligned with the statement. We will not be making any further changes until we have completed our consultations with industry and members of the public. The guidelines will then be updated to align with the new policy intent.”

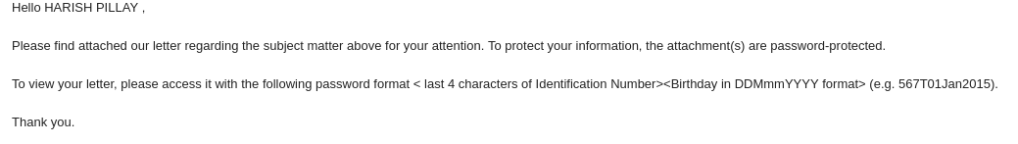

Using NRIC + Date of Birth as a password protecting scheme

Here’s an example of the misuse of NRIC + DOB for password protecting a document. In this instance it is a phone bill (duh!!!) and why the telco took that path, I have no idea.

This type of NRIC+DOB is also done by banks.

They give a false sense of security and privacy.

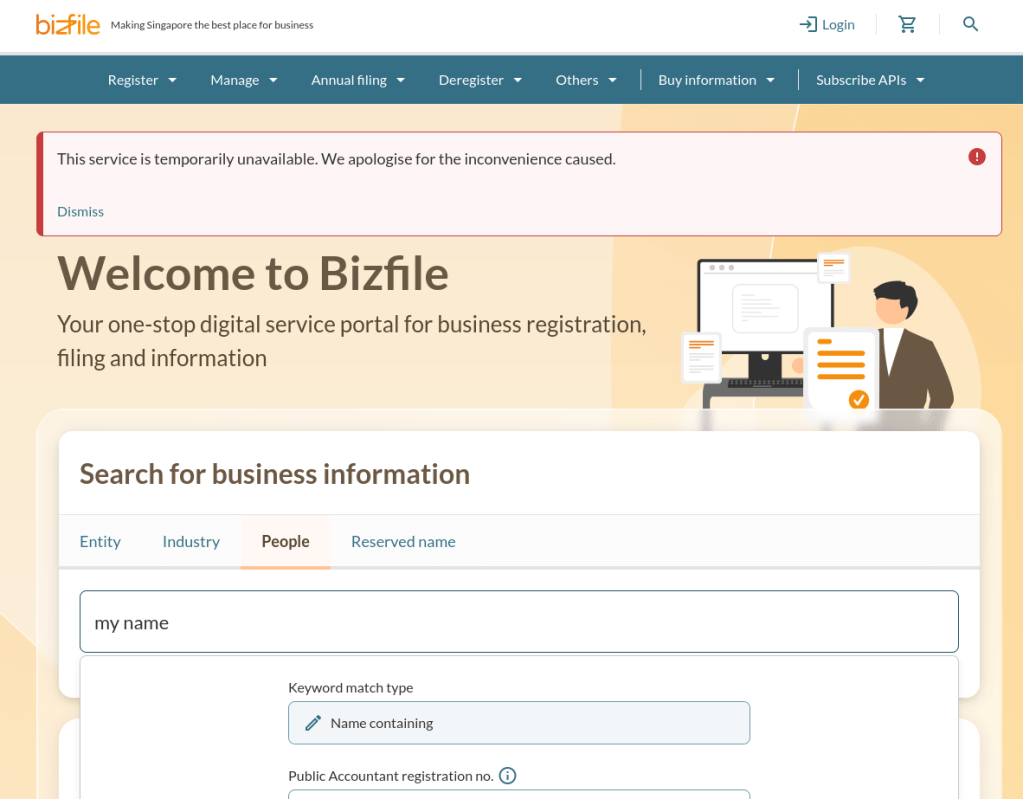

This entire episode of the value of masking of NRIC numbers stemmed from another government agency, the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority (https://www.acra.gov.sg/)’s wrongly pre-empted decision to unmask the NRICs of when one searches for business information (https://www.bizfile.gov.sg/).

Last week (from about 9th December 2024), ACRA, instead of masking NRIC numbers when someone’s name is searched for, it lets the entire number be visible. I did check for a few names and found their NRIC numbers.

But, on 12 December 2024 or so, as is viewable in the screenshot below, when the “People” tab is clicked and “my name” entered in the name field, the system now returns “This service is temporarily unavailable. We apologise for the inconvenience caused.”

The argument made by MDDI and PDPC that masking NRICs is not useful anymore, fails to make any sense.

The ACRA site had provided previously, the Name and masked NRIC numbers. Following a payment of S$33, you get the whole set of details of the individual for the purposes of validating a business or business involvement. All of those are valid use cases for which the entire NRIC should be made known.

The $33 is a speed bump, to add a cost to anyone wanting to find info about an individual.

One could argue that, given my example above to have an educated guess and by building a table of all possible numbers, the full NRIC can be found, so why mask it?

The current, or previously recommended, masking method S****NNNC, can be made useful if the check letter is omitted. Everything pivots on the check letter. Masking the check letter would widen the amount of numbers that will be matched. The table lookup will make it trivial.

The NRIC number space is limited. Name spaces, however, are almost infinite. Mapping NRIC to Name space gives opportunities for abuse if those NRIC numbers are used other than as a unique identifier.

The NRIC numbers never expires (even upon the death of the person). As long as NRIC numbers are used as part of “password locks” or any other hare brain ideas, we have a problem.

Once those practises are stopped, we can freely share NRIC numbers in full or not.